Media vita in mortis sumus. In the midst of life we are in death.

Death of a living year.

Death of ambition. Death of routine. Death of tradition.

Death of certainty. Death of youth. Death of womb.

‘Traditional knackeries which collected dead and casualty stock…have gone out of business.’(1)

How do we dispose of the carcases of identities— of identities we once held, never held, merely imagined —when John McLinden says, “The Government has made it clear there will be no assistance for the knackery trade”?(ibid.)

He said that in 1991. The words were published in a newspaper article that has been cut and pasted into an archive held by the National Museums of Scotland.

Is this a place of the dead, or a place that sustains life?

Does my quoting these words bring an identity back to life, salvage a corpse? Is it an identity John McLinden still wears, or has he hung it in the back of his closet a long time since, wearing it only for funerals and hoping never to wear it more?

This year, for the first time, neither of my children will be home for Christmas.

I flick to the Spring newsletter of Fletcher’s Deer Farm, Reediehill, Auctermuchty, in which the farmers write about their position during the foot-and-mouth outbreak of 2001.(2)

It is snowing.

White is the colour of textiles worn by the dead…red is the colour of textiles offered to the dead.(3)

Last night, I wore white, double cotton pyjamas, made in Sri Lanka. Although they feel comfortable, warm, the white is luxurious because it is probably impractical and, quite possibly, polluting.

I think of practices; of ayurveda, and life in a small village, off-grid in the Sri Lankan jungle, where I woke to the gentle paddling of the turtle who lived under the floating hut, emerged from white sheets sprinkled with flower petals, drank blue flower tea, swam in the lake to the sounds of the Buddhist monastery on the hill, and where the local monkeys threw fruit and branches at me whenever I tried to practise my recorder playing. There I felt fit, relaxed, alive.

That was beforetimes. Before the first pandemic of our lifetimes. Before we began to feel the real collapse. I lost so much.

Many others lost so much more.

We all lost.

What do we hold to now?

‘Primark saw total sales grow by 43% year on year to £7.7bn for the 52 weeks to 17 September 2022, citing that normal customer behaviour had resumed after the pandemic’.(4

Normal customer behaviour. Grabbing as much cheap, synthetic fashion as possible— to recover lost identities, to grasp at imagined identities, to realise something, to make something tangible. Momentarily.

When did this become normal? Normalised. By whom, for whom, for what?

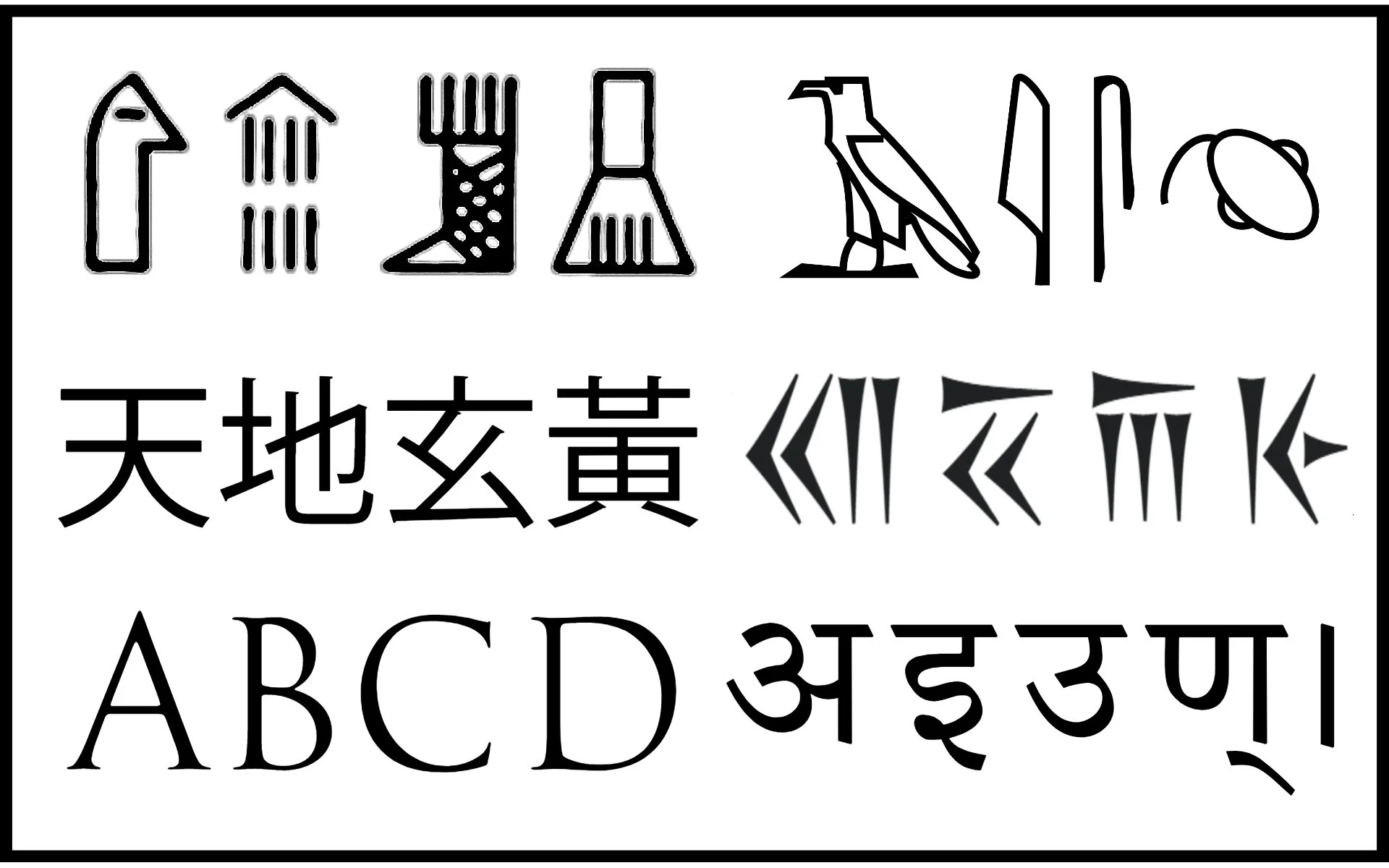

Identity; being a sense of belonging, consistency, differentiation, self-esteem, assertiveness. Having symbols, language, religion, habits, customs, reference groups, sexuality, values, norms, historical memory, work. Committing oneself, integrating oneself, confronting oneself, deciding on, getting to know oneself, recognising one’s self, actualising one’s self, growing. Participating in social rhythms, everyday settings, settings which one belongs to, stages of maturation.(5)

Identity. Politics. These clothes are made of oil. Oil. Slick. Sick. Sticking to our backs.

It cannot hold. It cannot even hold colour, only absorb it. It is the absence of light, the absence of identity. In my professional life, the wearing of black gave me permission to absorb the identities of others. To don their mantles. Momentarily. Their colours have never been mine.

Hold fast to what cannot hold? Hold fast or let go? Let go and learn to live differently. See differently.

‘Many people may consider clothes and colour unimportant and trivial; in isolation and taken out of context, they are. But as part of a full life, which to me means a life composed of many simple small pleasures, clothes and colour are at least as important as food and drink, but perhaps nearer, in their source and in the senses they satisfy, to music, poetry and painting.’(6)

Last night an engineer noted we were both old enough to remember life in other materials, other colours. That is important. That understanding of affordances, that haptic experience, that’s the gift we must pass to the young.

Red as the colour of blood and consequently of the living.(7) Red ribbons wrapped around Greek stele. To ward off evil?(8)

Death. Life. Rebirth.

Recycle. Renew.

Circular economies of wisdom.

Reveal. Expand. Reflect. Engage. Participate. Evolve.(9)

‘…the world in which we had been living for the past six years was going to change, I thought, rapidly…I felt a tremendous urge to be actively part of this emerging world…’(10)

1 The Scotsman. 15 jobs go as knacker business closes,’ article in The Scotsman.08.02.1991.

2 National Museums of Scotland. Scottish Life Archive. 68G Animal By-products. Furs and Pelts: Deer Farming; Carcas Disposal; Rare Breeds; Taxidermy. (FIF) NO2013(58).

3, 8 Andrianou, D. (2012) ‘Eternal Comfort: funerary textiles in late Classical and Hellenistic Greece’, in M. Carrol and J.P. Wild, Dressing the Dead in Classical Antiquity. Amberley, U.K: 42-62

4 Burke, J. (2022) ‘Primark sales rise’, article in drapersonline.com. 08.11.2022

5 Max-Neef, M. (1986) Human Scale Development. Dag Hammerskjöld Foundation.

6, 10 Klein, B. (1965) Eye for Colour. Bernat Klein Scotland with Collins, London:14, 46

7 Johansen, F.J. (1951) The Attic Grave-Reliefs of the Classical Period: An Essay in Interpretation: Copenhagen:116

9 Strauss, C.F., and Faud-Luke, A. (2008) ‘Principles of Slow Design — A New Interrogative and Reflexive Tool for Design Research and Practice’